Cripples, Idiots, Lepers, and Freaks: Extraordinary Bodies / Extraordinary Minds

(Not about me nor Pearlsky. Things have been tough, really trying to get back to the blog. Stick with me, please.)

Thursday, March 22 – Friday, March 23, 2012

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York

Could disability be, as Susan Wendell writes, “valued for itself, or for the different knowledge, perspective, and experience of life” it gives rise to? This conference seeks to continue—and to expand—conversations about the cultural meanings and possibilities of impairment, as well as the ways that the disabled body becomes a locus for uneasy collaborations and tensions between the social and the scientific. What critical and theoretical perspectives can be brought to bear on human variations that are, or have been, subject to medical authority or understood as requiring intervention? Emphasizing an interdisciplinary approach to “disability,” we seek papers from graduate students across the humanities (English, art history, music, etc.), social sciences (history, sociology, political science, etc.), and applied fields (law, education, medicine, etc.). We welcome papers on topics ranging from the aesthetics of illness in medieval literature to the politics of disability in South Park, from the cultural fascination with autistic savants to race, impairment, and spectatorship in freak shows.

Possible paper topics include:

Genre, Aesthetics, and Disability: poetics; visual art, photography, and spectatorship; life writing and illness narratives; metaphors and representations of disability; disability and performance; “outsider art”; impairment and artistic production; comedy and disabilityPedagogy and Disability: teaching disabled authors; writing the body; student embodiments, teacher embodiments; “coming out” and “passing”; disability and composition studies; “special” education

Sexuality, Desire, and Disability: pleasure and the extraordinary body; voyeurism; fetishism; freak shows; sexual practices; queering disability

Epistemology, Subjectivity, and Disability: genius and savantism; the body in pain; affect; “terminal” illnesses; acquired impairments, congenital impairments; stigma and otherness; autistic minds; mental “illness” / mental “health”; trauma, violence, and disability

Intersections of Identity: masculinity and disability; femininity and disability; pregnancy, motherhood, and impairment; race and disability; class and disability; queer identities and disability

History of/and Disability: historicizing disability; historically specific impairments (e.g. hysteria); period-specific studies of disability (e.g. early modern); eugenics; race and/as impairment; evolution and “degeneration”; taxonomy and natural history

Medicine, Science, and Impairment: medicalizations of race, class, sex, body size; addiction and disability; medical and scientific discourse; doctor / patient interactions; concepts and problems of the “cure”; diagnostic manuals and other taxonomies; the human / animal divide

Disability Activism / (Bio)politics: rhetorics of “disability”; activist art; reproductive rights; genetics and eugenics; euthanasia; healthcare; war, disability, and the making of populations; impairment-specific campaigns and organizations

Technology and the Impaired Body: technologies of reproduction; cyborgs; prosthesis; body augmentation / body modification

Please submit 250- to 500-word abstracts to ESAConference2012@gmail.com < mailto:ESAConference2012@gmail.com> by December 5, 2011.

* * *

The conference, sponsored by the English Student Association of the CUNY Graduate Center, will feature concurrent graduate panels on the afternoon of Thursday, March 22, and all day on Friday, March 23.

The keynote address on Friday evening will be delivered by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, and on Thursday evening a plenary panel will discuss the present and future of Disability Studies. Plenary panel members include CUNY scholars Sarah Chinn (English, Hunter College), Ruth O’Brien (political science, the Graduate Center), Victoria Pitts-Taylor (sociology, Queens College and the Graduate Center), Talia Schaffer (English, Queens College and the Graduate Center), and Joseph Straus (music, the Graduate Center).

All conference events will take place at the CUNY Graduate Center in midtown Manhattan.

Please visit the conference website ( http://esaconference2012.wordpress.com/) for more information. If you have any questions, please email the conference co-chairs, Marissa Brostoff, Andrew Lucchesi, and Emily B. Stanback at ESAConference2012@gmail.com < mailto:ESAConference2012@gmail.com>.

No comment from me.

Sticking.

Deep. In a Piled higher (and) Deeper kind of way.

I will read the rest of the comments with interest.

Who knew such conferences went on?

I don’t know. I don’t think I could handle a whole conference on disability studies as a discipline. But that’s just me.

I hope it’s ok to post this – I’m a disability studies student in the UK. There’s an old debate in the area about why we do disability research – my school broadly seems to come down on the side of disability research only being justified when it aims to improve disabled people’s experiences/can be used as a tool against disabled people’s oppression in society. One of the reasons I follow blogs like this one (apart from Single Dad’s excellent writing skills!) is to try and get a better sense of the day to day realities of life with people with multiple impairments. I come from a social policy background rather than sociological – and sometimes wonder about stuff like the above, particularly in the context of cognitive disability. I wonder how far this conference strives to be accessible to people from a non-academic background, disabled or not, but all the efforts I’ve seen towards inclusivity in research would seem to fall short where individuals like Pearlsy are concerned. I wonder if anyone would mind sharing their thoughts on what meaningful inclusion in disability studies research for people with severe cognitive impairment might look like?

“Could disability be, as Susan Wendell writes, “valued for itself, or for the different knowledge, perspective, and experience of life” it gives rise to?”

Well…it could be…but that just gets the crips all uppity, don’t it?

Thanks for this info – a couple of my disabled friends are writers, and may be interested in this.

And *hugs* if you want them

Damn. Not a whiff there of the notion that disabled people are, ya know, people. With their own individual agendas and perspectives. Not to mention that some of us move back and forth across the disability line, in both directions.

I’m glad I got out of academia when I did. Not that health care is exactly a bullshit-free zone.

Hey, all.

I’m one of the conference organizers and came across this blog quite by accident, but wanted to respond to a couple of things.

Debs515–Your question is the one that got me into disability studies in the first place. My brother is severely autistic and at one point had back surgery that left him paralyzed for some time (his mobility has improved vastly over the past ten years). We’re very close, and when I was first exposed to disability theory in college I felt strongly that much of it didn’t account for (or even leave any room for) his experience, either of severe autism or of having multiple severe impairments. The question of inclusion when it comes to severe cognitive impairments is a difficult one but an important one, and one I hope that people in disability studies will consider more often. (It’s a topic I’m very much hoping someone will address at the conference, in fact, and encourage you to submit an abstract if you think you might be able to make it to NYC.)

Elizabeth and Barbara–When I first got into disability studies I found it unbelievably overwhelming because the field addresses questions that hit so close to home, and, I thought, sometimes got it really wrong. But I do believe it’s important work and has the potential to effect real changes in the lives of people with diverse impairments and experiences.

For me, the important thing is to talk about disability, even if people disagree, and to question the place of “disability” in society. I think that one of the main reasons that modern societies are structured as they are (i.e. not very inclusively) is because of how disability is and has historically been represented, how we are taught (and encouraged) to think about disability, and how we are taught (and encouraged) to talk about disability. These are central topics to those of us who are engaged in disability studies, and I don’t think I’m alone in believing that if we (collectively) begin to think differently about “disability” we can more easily and fully effect real social change re. disability. (e.g. I suspect that a legislator with no intimate experience of disability who also grew up seeing standard representations of disability on television, in the newspaper, etc., would be hard pressed to understand why equal education for a disabled student could be thought of a right and not “special help” given by a compassionate society. And if disability studies continues to open up conversations in the college classroom and in the media, this might begin to change.)

So for me, any chance to talk about disability–in a conference, in the college classroom–is a chance to raise difficult questions and talk about issues related to disability. Of the many students I’ve taught as part of my graduate work, I’m not sure how many walked away with a totally changed view of disability. But I do know that they had to spend a lot of time talking about, writing about, and thinking about the ways that “disability” is viewed in society, the ways that they’ve reacted to and viewed disability themselves, and some of the ways that disabled individuals experience disability. And they also had to grapple with the idea that people like my brother are just as human as they are–which I can only hope may make a difference if one of my former students encounters disability in the future, as is bound to happen.

I could keep writing all morning–and into the night–but I’ve got to get to work. One last comment, though–

Lila, our intention with the call for papers was to keep things broad because we all believe that there’s a wide, wide, wide diversity of experiences of disability, and agendas, and perspectives–and we want to encourage people to talk about things that don’t usually get talked about in disability studies venues. It seems that didn’t come through in the call for papers, but I hope it will in the way that we put the conference together.

Emily

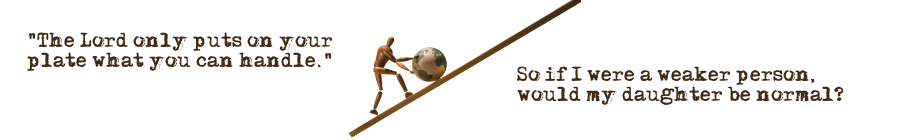

P.S. Just read the “Morons Say the Darndest Things” post–

These are exactly the kinds of things I hope (and believe) will be changed if we start talking about “disability” in a more nuanced and realistic way in the classroom and in popular media. Some (many?) people may continue to say ignorant and often offensive things–but it’ll give a chance for people who are more thoughtful to understand what they’re really saying when they say such cringe-worthy and often pain-inducing things.

Many of the most hurtful and offensive things I’ve heard from college freshman–e.g. “Okay, fine, maybe disabled people are actually really human beings, too, but I’d never ever save a disabled person from drowning if I could save a normal person”–often turn out to be the result of never ever having talked about disability and never having had to think about what they’re saying and why.

I grew up with daily contact with autism and other cognitive impairments, playing autistic games with my brother and having dinner at his classmates’ homes. But for a lot of people I’ve met, Forrest Gump or Rain Man is the closest they’ve ever gotten to thinking about cognitive impairment…